What’s Cooking – A Colonial Recipe

OVERVIEW:

The recipe page from The Ashfield Recipe Book allows students to gain information about colonial life. In analyzing this primary material example, students will use a recipe page to find out about colonial foods and daily practices and employ mathematical applications in everyday life. They will compare and contrast the world they know today with the past.

OBJECTIVES:

Read an historic object for clues about the pastStudents will be able to:

- Explore Colonial and modern techniques, vocabulary, and ingredients of cooking and recipes

- Gain understanding of the challenges of cooking in colonial times and modern adaptations.

WARM-UP ACTIVITY

Students discuss recipes and cookbooks to gain preliminary information before analyzing the colonial recipe page.

Guiding questions:

- Where do we find recipes? (family, friends, cookbooks, magazines, newspapers)

- Why do we need a recipe? (to get direction, to know amounts, number of people served)

- What different types of cookbooks are there? (ethnic, type of cooking such as baking, stews etc., type of foods such as vegetable, fish)

ACTIVITY #1 FAMILY COOKING

Curriculum Standards

- WR2 Use information, technology and other tools

- WR3 Use critical thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving skills

- LA3.1 Speak for a variety of real purposes and audiences

- LA3.2 Listen actively in a variety of situations

- LA3.4 Read various materials and texts

- LA3.5 View, understand, and use nontextual visual information

- M4.1 Pose and solve mathematical problems in everyday experiences

- M4.5 Use mathematical tools to enhance mathematical thinking

- M4.9 Understand and use measurement to describe and analyze phenomena

- M4.10 Use a variety of estimation strategies

- S5.2 Plan experiments, conduct systematic observations, interpret data

- S5.4 Develop an understanding of technology

- SS6.4 Acquire historical understanding of societal ideas and forces

- SS6.5 Acquire historical understanding of varying cultures

- SS6.6 Acquire historical understanding of economic forces

Have the students ask family or friends for information about when and how they learned to cook. This could be done as a formal oral history project or as simple questions. Consider if the interviewee learned from one person (and who), are self-taught, don’t cook much, use cookbooks, share recipes with others, keep a card file of new recipes, are interested in teaching someone else to cook, or if the recipes are connected to the family history (specific family traditions, holidays, or ethnic background). Have the students share their information with the class. Create a bar graph comparing the information.

ACTIVITY #2 READING AN OBJECT

Curriculum Standards

- WR3 Use critical thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving skills

- LA3.1 Speak for a variety of real purposes and audiences

- LA3.2 Listen actively in a variety of situations

- LA3.4 Read various materials and texts

- LA3.5 View, understand, and use nontextual visual information

- M4.1 Pose and solve mathematical problems in everyday experiences

- M4.9 Understand and use measurement to describe and analyze phenomena

- M4.10 Use a variety of estimation strategies

- S5.2 Plan experiments, conduct systematic observations, interpret data

- SS6.4 Acquire historical understanding of societal ideas and forces

- SS6.5 Acquire historical understanding of varying cultures

- SS6.6 Acquire historical understanding of economic forces

Background information

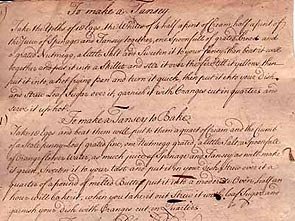

In colonial times a recipe book was kept by the mistress of the household. It was her guide to cookery as well as her treasury of family recipes. Most women did not own a printed cookbook such as the ones we see today. Cookbooks were expensive and of limited availability. When a young woman left her home to be married, she would copy her mother’s recipes to take with her. This recipe is from a collection started by Isabella Morris Ashfield (1705-1741). The collection was passed on to her daughter-in-law Elizabeth (1729-1762). These recipes are usually for large social family or ceremonial gatherings such as weddings.

(Resource for the recipe – The Ashfield Recipe Book, Collections of The New Jersey Historical Society. Background information from Pleasures of Colonial Cooking Prepared by the Miller-Cory House Museum and The New Jersey Historical Society. NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1982.)

Guiding Questions:

Look closely at the recipe page. What clues show that this recipe page might have come from a long time ago? (Page looks worn on edges, handwritten, some of the terms are unfamiliar -spinage, tansey, loaf sugar, in blood pudding – penny loaves, unfamiliar measurements – either a grated nutmeg, or 1/2 nutmeg, instruction to “stir it over the fire”)

How does this recipe page look compared to recipes today? Give examples (handwritten, splotches of ink on page, the recipes are listed in a number order, not by topic, measurements are larger -18 eggs, quart of milk; less exact measurements such as “one spoonfull” and “sweeten to taste,” “1/2 nutmeg,” “a little thyme, winter savory” etc.)

What might these non-exact measurements tell us about the cook? (experienced in cooking, know how much “a little” is or how big a “spoonfull” is.)

How would you find a specific recipe in this book? Could you find one of a specific type? (Would have to know the book or flip through the pages, the recipes are only in order of when they were written in)

How many recipes did the owner have by the time of this page? (82 – 80, 81, and 82 are marked on the left side of the page) How many recipes might one find in your home?

Look at the “To make a Tansey” recipe

To make a Tansey

A tansey is an omelet-like pudding flavored with tansey, an aromatic, bitter herb. (transcription below)

Take the yolks of 18 eggs, the whites of 4, half a pint of cream, half a pint of the juice of spinage and tansey together, one spoonfull of grated bread, and a grated nutmeg, a little salt, and sweeten it to your fancy. Then beat it well together and put it into a skillet and stir it over the fire till it yellows. Then put it into a hot frying pan and turn it quick. Then put it into your dish and strew loaf sugar over it. Garnish it with oranges cut in quarters and serve it up hot.

How many people do you think this is for? How can you tell? (A guess – 2-3 eggs per person 18 eggs in total, 6-9 people. The saved recipes were usually the special recipes – used for large social family gatherings)

What do you think spinage is? (spinach)

The other unfamiliar term is tansey – tansey was an aromatic, bitter herb not available today. Tansey is both the name of the recipe and the herb used in the recipe.

Look at a picture of a whole nutmeg (in an encyclopedia or a book about spices) and compare it to already grated nutmeg. How do these compare? How would you use the whole nutmeg mentioned in recipe? (grate it)

Why don’t people usually buy a whole nutmeg today? (easier to buy already grated, recipes call for exact measurements)

Why do recipes have exact measurements? (more people cooking, with different levels of experience. Also, people experiment with cooking unfamiliar to them, helps to have exact measurements when trying something you don’t know)

What hint is there that the tansey was cooked over a flame in an open hearth? (“stir it over the fire”)

What are the last toppings to be put on the tansey? (loaf sugar and orange quarters)

Look at the sugar tongs in the kit box. These were used to get sugar pieces from the loaf sugar. Loaf sugar was a compact cone of sugar. How do you think the tongs were used? (The pincers were used to break off smaller pieces from the loaf sugar)

One spice is used to make Tansey which was not available to everyone in Colonial America. Which do you think this is? (Nutmeg – was imported from Grenada and Brazil and available to upper classes) Where do we get spices today?

Modern version of the tansey recipe

The Ashfield recipes were tested and adapted by the Miller-Cory House Museum in Westfield, New Jersey by their Open-hearth Cooking Committee in the 1980s. This is their adaptation.

Spinach Omelet

- 6 eggs

- ½ cup heavy cream

- ½ cup spinach, cooked, drained, and chopped

(½ package frozen spinach, thawed) - ¼ teaspoon nutmeg

- ¼ teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 1 orange, quartered

Beat the eggs and cream together lightly with a fork. Stir in the spinach, nutmeg, and salt. Melt the butter in an omelet pan or heavy skillet over high heat. When the foam subsides, pour in the egg mixture. Reduce the heat and tilt the pan until the eggs are set. The pan may be covered to help set the omelet top. Fold the omelet in half and slide it onto a heated serving dish. Garnish with orange quarters. Serves 2.

Look at the colonial recipe and its modern version. How do they compare? (in modern – no tansey, specific measurements, spinach – not juice of, no sugar, says how many people served, smaller amounts, cooked over high heat not a flame)

How do you think the taste results of the two recipes would compare?

How would you adapt the modern recipe to serve 9 people?

ACTIVITY #3 ROLE PLAY

- WR3 Use critical thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving skills

- WR5 Apply safety principles

- LA3.1 Speak for a variety of real purposes and audiences

- LA3.2 Listen actively in a variety of situations

- LA3.5 View, understand, and use nontextual visual information

- S5.2 Plan experiments, conduct systematic observations, interpret data

- S5.4 Develop an understanding of technology

- SS6.4 Acquire historical understanding of societal ideas and forces

- SS6.5 Acquire historical understanding of varying cultures

- SS6.6 Acquire historical understanding of economic forces

Background information

Colonial cooking occurred in an open hearth. It was important to have a good quality fire to make a good bed of coals. Since the hearth was used as both a stove and oven, a pie could be baking in the back of the hearth, stew in a kettle hanging from a crane, a footed kettle has food cooking inside while more food is roasting on a spit in front. The tansey was placed in a skillet and held over the fire. The woman cooking was dressed in a long dress, with long sleeves and long hair.

Imagine or act out what the woman cooking would have to be careful of as she cooked her tansey (fire – to her long skirt, sleeves and hair; aware not to burn feet when reaching into the flame) How could she protect herself? (Tie her hair and sleeves up, wear strong shoes, have buckets of water and sand available near the hearth to stop any flame). Add other roles. Who brings in the wood or the bucket of water? How would the food be served? What would the reactions be to eating the tansey? Role play a large get-together.

Activity Extensions

- Tansies were traditionally made at Easter. Have students collect recipes, or simply the names and descriptions of dishes made for specific holidays or events. Discuss why specific food choices were made (birthday – the birthday person’s favorite food, some religious-based meals include foods which carry specific meaning, in some meals foods are determined by availability of the product (tomatoes in the summer, brussels sprouts in the winter, or from different countries).

- Collect recipes which use different herbs and spices. Buy samples of the different spices and have the students guess what they are from the smells. Discuss which ones are familiar or not and why. Compare recipes to see what spices are used in what types of recipes.

- Grow herbs in the windowsill. Basil grows very easily and is aromatic. Pesto is simple to make with a blender, basil, olive oil, and walnuts or pine nuts.

- Research nutmeg or other spices mentioned in the recipes on the Ashfield recipe page. Trace where these spices come from in order to get to the United States. Find how different routes were developed to make spices available to colonial America. Mark these routes on a world map. Research what payment was made by Colonial Americans in return for the spices.

- Design a tool to grate a whole nutmeg and to store what has not been used.

- Design and sew a pot holder for the colonial kitchen.