Cudjo Banquante: African Enslaved Soldier Business Owner

A Collaborative Project

Cudjo Banquante:

African

Enslaved

Soldier

Business Owner

Cudjo Banquante’s story is one of hardship and suffering. For most of his life he was in bondage. Captured and enslaved from his home in Africa, he endured life-threatenening imprisonment and a dangerous ocean voyage shackled to a slave boat. He was enslaved for many years, even substituting for his “owner” as a soldier in history-making battles of the Revolutionary War.

But despite his struggles, Cudjo’s story is one of the triumph of the spirit. He not only survived a lifetime of adversity, but thrived and prospered as a free man late in life.

Cudjo sets an example for all of us.

African

What’s in a name?

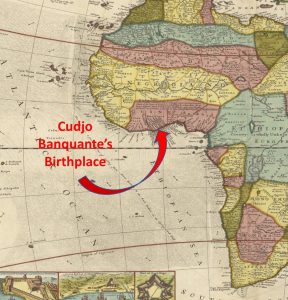

Cudjo Banquante’s name says a lot about his history.

His first name, “Cudjo,” is a dialectical variation of “Kwadwo,” a traditional Akan name given to a boy born on Monday. “Cudjo” in its native form is written as “Kudwo,” the “dw” pronounced as a “j” or “gy.” The Akan language is unique to the area of what was then the Gold Coast, today Ghana. The name Cudjo is common in Ghana, though extremely rare anywhere else.

Cudjo’s last name also points to his roots in the Gold Coast. His last name in its native form would be “Bakwante.” It is a compound name, comprising “Baa” and “Kwante” (an appellation or title). This name is found in the Akan culture of Ghana, though it is exceedingly rare and used mostly by royalty. King Baa Kwante Agyeman ruled in the early 1700s. In Apinaman, there was a King Baa Kwante in 1837. Even recently there was a Baa Kwante Agyeman, a royal of Kyebi. While his lineage in Africa cannot be confirmed in records, his name suggests that he descended from African royalty, as Cudjo frequently claimed.

Excerpt from 1710 map of Africa, fom the Evolution of the Map of Africa Collection, Princeton University

https://lib-dbserver.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/maps-continent/1710%20moll.jpg

Ethnic Warfare

Intense warfare between ethnic groups cursed Cudjo’s homeland in Africa when he was a young child. The Asante and Akyem communities, filled with revenge, fought bitterly for territorial control. It was common practice for prisoners taken at battle to be sold into slavery. Other southern groups soon joined the “capture and sell” fever, creating an environment where basically anyone at the wrong place at the wrong time could be game for slave hunters. This was quite a convenient arrangement for the European slave traders, who profited from the war without needing to put their own lives in danger. A strong, young man with a royal heritage, like Cudjo Banquante, would have been quite a catch and fetch a premium price.

Enslaved

Cudjo’s Gate of No Return

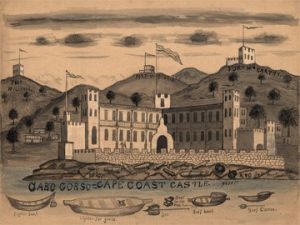

The details of Cudjo’s capture and enslavement are not known, but once captured he would have been marched in shackles and chains from his homeland to the coast and held in a “slave castle” built by European slave traders. These fortresses warehoused enslaved prisoners for weeks or months until enough were collected, a ship was available, and a slave trader bought them for transport across the Atlantic. Cudjo might well have stayed in one of the most notorious of these, Cape Coast Castle, which remains standing today. This fortress would be Cudjo’s final stop in Africa before crossing the Atlantic Ocean. There he would have been shackled in an underground dungeon, a space of terror, death, and darkness.

Cape Coast Castle, and Forts William, Victoria, and McCarthy, Gold Coast, mid-19th century. From Drawings of Western Africa, University of Virginia Library, Special Collections, MSS 14357, no 7

https://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0103

Modern day image of Cape Coast Castle, from https://breathlist.com/africa/ghana/explore/unesco-world-heritage-sites-to-visit-in-ghana/

A Treacherous Journey

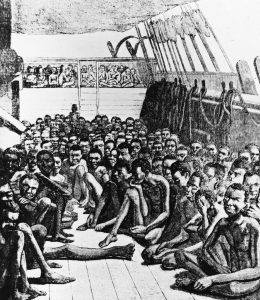

Eventually Cudjo was forced to board a slave ship to cross the Atlantic on a dangerous voyage under horrible conditions, a trip that became known as the Middle Passage. Chained together, packed shoulder to shoulder in dank squalor, and fed little, it is estimated that only one third of those who boarded survived the six- to eight-week trip.

The crowded deck of a slave ship, Hulton Archive/Getty Images

https://www.history.com/news/transatlantic-slave-first-ships-details

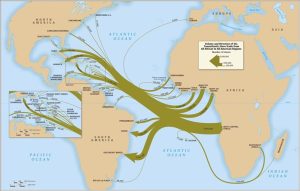

Most slave traders delivered their human cargo to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, where the enslaved worked in the intense tropical heat under terrible conditions, sometimes wearing an iron head mask to prevent them from eating any of the precious sugar cane. Like so many others, Cudjo might have spent time somewhere in the Caribbean before eventually being brought to North America.

Volume and direction of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from all African to all American regions

From slavevoyages.org

https://www.slavevoyages.org/static/images/assessment/intro-maps/09.jpg

Reprinted from: David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven, 2010)

Whether he came by way of the Caribbean or not, eventually Cudjo was sold to the distinguished and wealthy Benjamin Coe of Newark. This was a time of explosive growth in the population of enslaved African-Americans in New Jersey.

Soldier

During the American Revolution, Newark was a very dangerous place because of its proximity to the British stronghold of New York City. Skirmishes, battles, and raids were frequent, and much of Newark was ravaged. Benjamin Coe’s house was burned to the ground by the British, and Coe fled over the Watchung mountains to the safer haven of Hanover in Morris County. Cudjo might have stayed behind in Newark for a time, according to Coe family records, but eventually he joined his “owner” in Hanover.

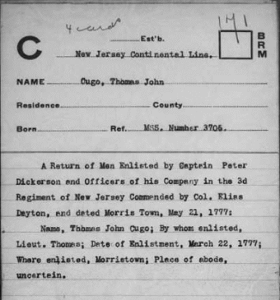

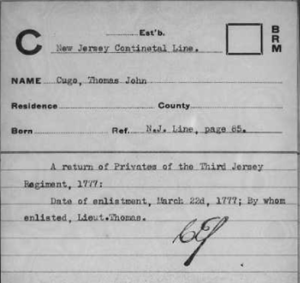

While in Hanover, on 22 Mar 1777 Cudjo enlisted as a Private in the Continental Army, serving in Captain Peter Dickerson’s company mustered out of nearby Morristown. When Captain Dickerson died in 1778, he was replaced by Captain Jeremiah Ballard, and Cudjo continued to serve under Captain Ballard.

What’s in a name (again)?

Spelling variations and phonetic interpretations of names were commonplace in Colonial and Revolutionary times. But a name like Cudjo Banquante must have been just too much for the American soldiers and officers to handle. They assigned him a variety of anglicized names, taking his first name and making it his last name, spelling it many ways such as Kugo, Cugo, Cuga, or Cutjoe. For his first name, they assigned him John, Jack, Thomas, or even Thomas John. Perhaps the name “Thomas” came from the fact that he first enlisted under Lieutenant Thomas.

A Brave Fighter

While there is clear evidence that Cudjo served in the army, details of his specific battles are scant. His unit served the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown in 1777 when Cudjo was in active service, he camped at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778. At the Battle of Monmouth in 1778, Cudjo was with Brigadier General William Maxwell’s Brigade, serving with more than 800 black troops in battle that day with the Continental Army. He defended Elizabethtown Point in 1778, guarded Paulus Hook (now Jersey City) in 1779, and served on the Sullivan Expedition into Pennsylvania and western New York in 1779. It is believed he took part in winning the Battle of Yorktown in Virginia in 1781.

Revolutionary War Slips, Single Citations of the New Jersey Department of Defense Materials

Film #569443, Image Group #8518951, familysearch.com

Excerpt from drawing of soldiers at the siege of Yorktown, from the diary of French officer Jean Baptiste Antoine de Verger,

Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-black-patriots-american-revolution

Business Owner

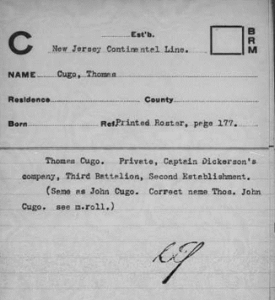

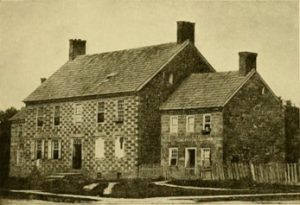

After the war, Cudjo’s “owner” Benjamin Coe returned to rebuild and restart his life. He rebuilt his home in Newark, a lovely brick home where Cudjo lived as an enslaved servant.

The Coe homestead which replaced the structure burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. From A Quiet Lady by Greg Guderian, posted on An Attractive Presence: The World of William A. Whitehead, https://wawhitehead.net/2019/02/28/a-quiet-lady/

Eventually Benjamin Coe’s son, also named Benjamin, granted Cudjo his freedom because of his service as a substitute soldier. This might have been around 1784, when the New Jersey legislature passed a law that freed all enslaved persons who served as soldiers on both sides of the Revolutionary War.

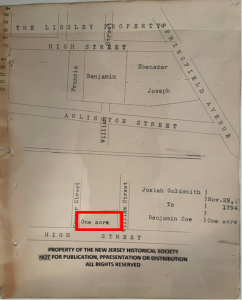

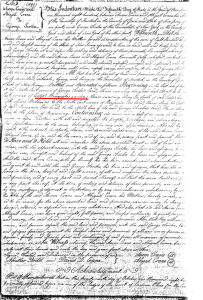

In 1794, Coe gave Cudjo a one-acre plot of land on High Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Boulevard) between Mercer and William Streets. Today, this property is the site of a former Greek church, directly across the street from Arts High School.

In his free life he proudly used his native Akan name, Cudjo Banquante, though sometimes in legal documents he allowed that he was also known as Jack Cudjo.

From New Jersey Historical Society MG 1421 Box 1 Folder 3: Coe Family Genealogy

When he finally received his freedom, Cudjo was about 70 years old and suffered a lifetime of hardship. Yet he had the strength of spirit to start a new life and build a successful business from scratch. He began importing and growing exotic plants and selling them to Newark residents. He established a reputation as an exceptional gardener and a very successful businessman, selling his plants to the wealthiest residents of Newark. His business must have been quite significant, because it is used as a landmark in deeds in the area, frequently called “Cudjo Banquante’s garden.”

This business distinguishes Cudjo as the first documented black business owner in Newark, perhaps even the first in the state of New Jersey. Cudjo is the best known of the 18 financially substantial black men in 1821 tax records. His home was valued at $400 in these records, a significant sum suggesting he lived a comfortable life at this time. By blazing a trail of independence and success in business, Cudjo set an example for many to follow.

Essex County NJ Deed Book G, page 245

Cudjo’s Family

Cudjo and his wife Mary raised a large family in freedom. Cudjo’s will names “two youngest sons” Peter and Joshua. One of the witnesses to the will was Jonas Cudjoe, probably an older son. Tax records indicate other Cudjos in Newark, Abraham and Pack, who were probably other sons. Son James died young. He had a daughter Mary, and possibly another daughter Hannah.

Cudjo’s Final Resting Place

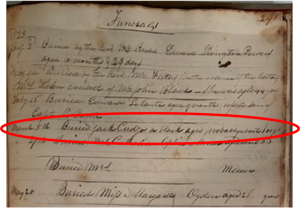

Cudjo died in Newark and was buried in the Trinity Church burial yard on May 5, 1823. The church record says he was “probably about 100 years” when he died.

Burial Record from Trinity Cathedral in Newark, NJ Papers, 1743-1973

From New Jersey Historical Society, Manuscript Group 882

Trinity Church was located in Military Park, with its burial yard nearby on a portion of land between Rector Street, old Saybrook Place, Park Place and McCarter Highway. The cemetery was in operation from about 1810 until the late 1800s. Gradually the cemetery was reduced in size and importance, diminished by commercial expansion. Graves were relocated at least three times. The cemetery had become completely overgrown and for all practical purposes, was forgotten. By the 1960s, the much-diminished place had become a tangled mess of broken headstones clogged with vines and heavy undergrowth, and almost completely hidden from view by surrounding buildings. A parking lot was eventually built over the site, and in the 1990s it was built over by the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC).

Today, the only evidence of the burial yard and those buried there is a glass monument on the NJPAC grounds with a long list of names of those buried there. A footnote at Cudjo’s name says “former slave who fought bravely in the American Revolution and was awarded land for his military service.”

Photo of monument on NJPAC property by Susan Bailey, Morristown Chapter DAR

Bibliography

Atkinson, Joseph, The History of Newark New Jersey: Being a Narrative of Its Rise and Progress. Newark NJ: William B. Guild, 1878, pg. 117.

Ayim, Kofi, Jack Cudjo: Newark’s Revolutionary Soldier & First Black Businessman. New Jersey: Reedbuck, Inc., 2011.

Bartlett, J. Gardner, Robert Coe, Puritan: His Ancestors and Descendants 1340-1910. Boston MA: published by the author, 1911.

Chen, David W., Jerseyana: A Frustrating Final Chapter in a 19th-Century Graveyard’s History in The New York Times, 26 Nov 1995.

Cummings, Charles F. Slavery in New Jersey: A Shame that Spanned Three Centuries in the Star-Ledger, Newark NJ, 10 Feb 2000. Online at https://knowingnewark.npl.org/slavery-in-new-jersey-a-shame-that-spanned-three-centuries/

Cummings, Charles F. Knowing Newark – Blacks in New Jersey: The Journey in The Star-Ledger, Newark NJ, 17 Feb 2000, page 3.

Cummings, Charles F. Black Trailblazers Wrote New Chapters in the City in The Star-Ledger, Newark NJ, 12 Feb 2004, page 3.

Cummings, Charles F. Black Pioneers Filled Ranks of City’s Who Was Who in The Star-Ledger, Newark NJ, 3 Feb 2005, page 3.

Cummings, Charles F., Mt. Pleasant Still Stands as Monument to Glories of the Past in The Star-Ledger, Newark NJ, 22 Apr 1999

Cunningham, John T., Newark. Newark NJ: The New Jersey Historical Society, 1988, pp. 79-80.

Epps, Linda Caldwell, Jack Cudjo Banquante, posted on Revolutionary Neighbors, Crossroads of the American Revolution, https://revolutionarynj.org/rev-neighbors/jack-cudjo-banquante/

Essex County NJ, Deed Book G pp 245-246, Aaron Crane and Abigail Crane to George Scriba.

Gigantino, James J. II, The Ragged Road to Abolition. Philadelphia PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016, pg. 197.

Grundset, Eric G. (ed. and project manager), Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War, A Guide to Service, Sources and Studies, Supplement 2008-2011, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2011, pg. 29.

Guderian, Greg, A Quiet Lady – An Attractive Presence, posted on The World of William Whitehead, wwhitehead.net, 28 Feb 2019, wawhitehead.net/2019/02/28/a-quiet-lady/

Hoskins, Barbara, Men from Morris County New Jersey Who Served in the American Revolution. Morristown NJ: Friends of the Joint Free Public Library of Morristown and Morris Township, 1979, pg. 52.

Lee, Francis B., New Jersey Archives, Second Series, Vol. 2, Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey. Trenton NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Co., printers, 1903, pg. 130.

New Jersey Historical Society, Manuscript Group 1421, Box 1, Folder 3, Coe Family Genealogy, map between pages 18-19, pg. 27, pg. 42.

New Jersey Historical Society, Map 346, Map of Estates of Benjamin Co Benjamin Coe.

Stryker, William S (ed.). New Jersey Archives, Second Series, Vol. 1, Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey. Trenton NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Co., 1901, pg. 352.

Stryker, William S., Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War. Trenton NJ: Wm. T. Nicholson & Co., 1872, pg. 177.

Trinity Parish Church entry book #19, under funerals 24 May 1813 to 15 Apr 1845. Held at the New Jersey Historical Society, MG 882.

U.S. Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783 accessed on ancestry.com. 02d Regiment, 1776-1783 (Folder 34); 3d Regiment, 1770-1780 (Folders 35-38). Digital pages 615, 620, 622, 624, 625, 628, 632 of 699.

Woodruff, George Coyne, History of Hillside N.J. and Vicinity. Hillside NJ: The Hillside Times, 1934, pg. 54.

______, 3000 Blacks Served in Continental Army, newspaper clipping in the Morristown African American Veterans file at the Morristown and Morris County Library, Morristown NJ.

______, Newark as It Was – No. 19 in Newark Daily Advertiser, Newark NJ, 8 Apr 1864.